Kurdistan 1986. Paradise Lost

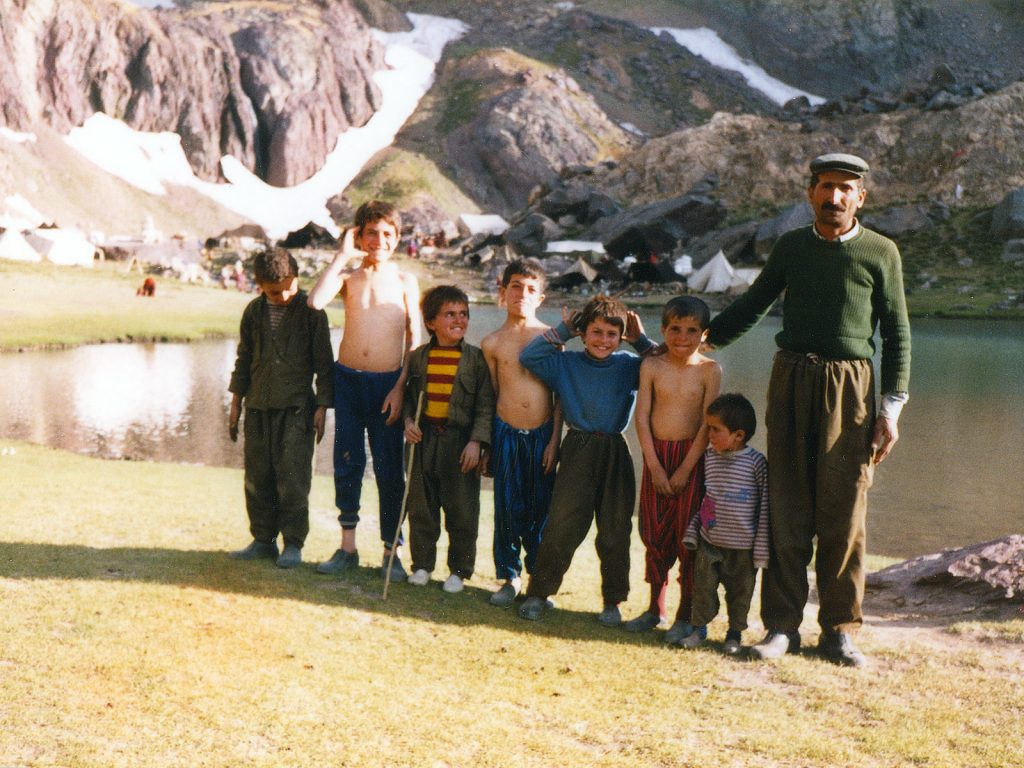

Scroll to the bottom for a downloadable PDF if prefered. This is an account of two summers I spent with semi-nomadic Kurdish pastoralists in the summer of 1985 and 1986. During each of the summers I spent about a month on Samdi Dag mountain in the Cilo-Sat range of mountains in Hakkari Province in the very south east corner of Turkey, in what was then it’s remote and anarchic borderlands with Iraq and Iran. The semi-nomads spent the winters in their village, called Ikiyaka, which was previously Sat koyu, on the southern flanks of Samdi Dag in a valley partly in Iraq. The village has ancient roots and there were many venerable walnut trees around the stone houses. It had previously been an Assyrian village and there were the ruins of a 12th Century church on its southern edge. During the warm spring the heavy winter snows, which buried the village, quickly melted and fed the surrounding pastures but by early summer these pastures were parched and only the irrigated terraced fields remained green. Then most of the families packed their black goat hair tents, cooking utensils and bed rolls and loaded them onto mules to make the journey up the steep, dry south flank of Samdi Dag to the main ridge crossing over to the northern flanks of the mountain, taking their herds of sheep and goats with them. The village would split into three groups or herding units each dispersing onto extensive pastures on the northern flanks of Samdi Dag where snowfields would persist late into the summer slowly melting and keeping the pastures green. As these snowfields retreated up the north side of Samdi Dag mountain, the semi-nomads would follow them, each herding unit moving camp, also called zozan, every few weeks so the herds would always graze green pastures. Towards the end of the summer in September the nomadic camps would be spread across the pastures at the top of the north side, often on large plateaus with glacial lakes beneath towering crags. I spent most of my time camping in the midst of one herding unit who finished the season at Sergera zozan , occasionally visiting another who ended the summer at Gaveruk zozan.

01. Ikiyaka village, formerly known as Sat koyu, is a small village of 80 houses in the wild borderlands of Turkey, Iraq and Iran deep in the northern Zagros Mountains. The village lies in Turkey but just a kilometre from the Iragi border.

Before going up to the mountains I had to spend a frustrating week in Yuksekova, a small town in the Province of Hakkari some 3 hours south east of the city of Van. It was on one of the transit roads used from Turkey into Iran so the road was paved between Van and Yuksekova. I found a basic room above a lokanta style restaurant at the main T junction in the dusty town. It was near the principal mosque and I could hear the slightly scratched gramophone recording coming from the loudspeakers on the minaret 5 times a day as the muezzin broadcast the call to prayer. I had been in Turkey long enough to find this important part of everyday life familiar, but still found different intonations and chants exotic and somewhat comforting in this seldom visited corner. My main concern in Yuksekova was to get permission from the authorities to go up to the Cilo-Sat mountains. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) had a paramilitary force based in Northern Iraq and SE Turkey and their army of outlawed insurgents were starting to attack Turkish government institutions. The Turkish military authorities were getting nervous about the border regions and were starting to limit access to them. Indeed a few remote border posts manned by Turkish conscripts and even some small garrisons had been attacked. At first I asked the Police but they were reluctant to help. “Yasak” they said. “It is forbidden”. Undeterred I walked to the Gendarmerie post which was like a small barracks. I was told to come back the next day to see the commander. Again he said “Yasak” but suggested I go see the Military at the barracks up the road. At the Military barracks I managed to get a meeting the next day with a senior officer. At the meeting he said that terrorist activity in the area was minimal at the moment and their intelligence did not see a threat but I would have to get permission from the Commando Unit officer stationed in Yuksekova and also the Gendarmerie officer again. With my foot in the door I went round to the Commando Unit and got the officers approval and a letter I could show to the Gendarmerie. After some 5-6 visits to the three security force barracks over as many days I finally had permission, albeit reluctantly given, to go up to the Sat Golu lakes, now called the Ikiyaka Golu, but was told not to venture onto the south side of the mountain.

While I was seeking permission in Yuksekova I spent my spare time wandering about the town and searching out shops and markets where I might buy supplies. When I finally had approval it was easy to obtain dried and canned food, a conical tent much used by road workers in Turkey, a carpet to line the floor of the tent, local blankets, tobacco, a large paraffin stove and a 10 litre container of paraffin. I had hoped to spend about 2 weeks up in the mountains, but knew very little about what I would find up there although I had been told there were nomads (göçebe) there, so I needed to be quite self-sufficient. Once I had everything I needed, I managed to get it all onto the old jeep style minibus which went to Oramar, now called Da?l?ca, every other day. It took 3 hours bumping along the rough track to the army post at Varegös. It was late afternoon when we got there and it was too late for me to go up to the mountains as the mules had already left in the early morning and some were just returning from the nomadic camps higher up.

The army post commander suggested I wait until the morning and hire a mule to take my stuff up. It was by far the most sensible thing to do but the army post commander was also reluctant for me to camp nearby. He suggested I continue in the jeep for another 2 km to the hamlet at Gürkavak and then get the jeep when it returned from Oramar the following morning. So I returned to the waiting jeep and carried on to Gürkavak where I was driven to an ordinary stone single storey village house and unloaded my stuff. It was an awkward evening as my Turkish was poor and my host English non-existent. A steady stream of men from other houses dropped in to see me like moths to a candle. My hosts fed me and I ate with the men of the household cross-legged on a carpet on the stone floor while the women served us. After the meal, I was shown a kapok mattress where I could sleep. To escape the limelight I went to bed early and wrapped up in my blankets. I had to endure the worst fleas and bed-bugs I had ever experienced that night. My hosts slept in the same room so I could not shine a torch or find somewhere else for fear of offending them. I could feel them crawling all over me, biting occasionally and had a restless night. I was glad to get up and escape in the morning when the jeep returned to take me back to Varegös.

02.Ikiyaka village lies on the south side of Samdi Dag, 3811m, one of the major massifs in the Cilo Sat range in Hakkari province in SE Turkey. Just to the south of the village is Iraq. On the north side of the mountain is the army post at Varegös on the track between Yuksekova and Oramar

There were a few muleteers at Varegös. They were largely from the village of Ikiyaka and spent the summer going backwards and forwards in 4 stages with each stage being about 3-4 hours. They left Ikiyaka village with fresh vegetables and firewood and climbed up the south flank of Samdi Dag to the pass by the pastures by Gaveruk, unloading their wares here. They then loaded their mules with a feta type cheese and some butter which was made at the pastures and headed down to Varegös, where these would be sold and taken to Yuksekova by tractor and trailer. The mules would then load up with flour and salt and return back up the mountain to the camps around the pastures and unload what was needed here before continuing on over the pass and down to the village of Ikiyaka. It was a tall order to do the whole journey in a day and the muleteers could easily do 2 or even 3 stages in a day. I found one who was heading back up to the pastures in the mountains and made it worth his while to take my baggage up rather than the load of flour. We loaded the mule, stuffing my baggage into hardwearing goat hair sacks, which were strapped each side of the saddle. It was hot down here in the deep valley and a relief to start walking south up the valley.

03. Half way along the road from Yuksekova to Oramar (Daglica) is the army post at Varegös. This was also where the semi-nomadic villagers of Ikiyaka traded their pastoral produce for flour. This is me and the mule I hired to take up everything I thought I needed for a month in the mountains.

A track went up the east side of the Rubarisin stream which tumbled down a rocky boulder bed. Even in midsummer it was quite powerful and full of snowmelt. It was clear and cold as it rushed down pouring over the boulders, but I noticed a dead mule in it curved round the upstream side of a boulder. After a short hour the valley reached a junction and the track headed up the east side for a short distance before it petered out into a path. It was up the west fork of the valley I wanted to eventually go but the path up there was steep, loose and not suitable for the mules. The muleteers led me and a few mules up the east fork to the track end and then beyond until the path forked with a branch going straight up the valley to pastures and encampments on the north side of Samdi Dag peak and another path going up over the ridge separating the two streams. We took the latter crossing the stream on boulders and then climbing quickly to the apex of the ridge with the mules straining. We stopped here and one of the mules carrying flour went amok and ran back down the slope with a frantic muleteer in hot pursuit. After our break we contoured around the ridge above the previously mentioned west fork, with its small steep rocky stream. Here the terrain became gentler and we could descend to the rocky stream and cross it in a rocky ravine and then follow the well worn path up steeper pastures into a hanging valley where there was a nomadic camp at the lip.

04. Leaving Varegös and heading up the Rubarisin stream into the Sat mountains. The path went to the left of the rocky ridge ahead and then crossed the stream and climbed up over the same ridge into the valley straight ahead before climbing out of the picture’s right and into the Hanging Valley.

My muleteer was a family member of one of these nomadic households so we stopped here and I introduced myself. Within minutes the whole camp had surrounded me There were perhaps 5 men, 10 women and 40 children, who were all jostling about excitedly at the front. I felt a bit overwhelmed by the attention. It was obvious to me there were very few visitors here. When I explained I was from the UK few had any idea where that was. Eventually one of the older men directed me to a large, black, goat hair tent which rose up from a circular rickle of stone a meter high, to which the fringe of the tent was draped over and tied down to. There was a gap in the stone enclosure about 3 meters long and a pair of wooden poles held the fringe of the tent aloft here forming a gaping mouth. I followed him in, took off my shoes and then sat cross legged on the carpet while a lady in a colourful Kurdish dress stoked the small open fire. It was not too dark in the tent and a relief to be out of the hot glare of the relentless early afternoon sun. There were a few more poles inside the tent holding the canopy aloft and carpets covered much of the floor with bedding rolls stacked up against the stones on the inside. It was smoky inside as the fire got going and the goat hair hessian hindered the smoke from rising. I made some small talk with the host as a drink of yoghurt and cold water (ayran) was prepared. My host’s name was Hussein and I guessed he was 45 years old, as was the lady preparing tea who was his wife and called Huri. Hussein seemed to be the senior man in the camp.

05. Hussein Donat was one of the first to greet me when I arrived at the Hanging Valley zozan. He had a large black woven goat hair tent here and invited me in for tea and to enquire what I wanted to do up in the mountains. He was to become one of my patrons.

Tea was served in small glasses on a large platter and there was a bowl with sugar lumps. A few more men joined us for tea and there was an endless stream of questions, of which I only understood a few. My Turkish was not up to replying to them so I had to get the small notebook out to illustrate my answers. I endured strained conservation for a good hour with Hussein’s wife often filling the tea glasses and me nervously rolling cigarettes and offering my tobacco around. Eventually I asked if I could stay in the camp and put my tent up nearby. Hussein muttered with the other men in Kurdish and then agreed I could. We went outside and he showed me where I could camp beside a few other tents near a small brook which meandered across the pasture after emerging from a nearby spring. As I put up my large conical tent, the whole camp appeared again and surrounded me. The 5 men and just one woman were the only ones who spoke Turkish and the rest could only speak Kurdish. The men had learnt it during their 3 years of military conscription, usually in the western or central areas of Turkey. The tent was a familiar one to the men, widely used all over Turkey. I was lent a central wooden pole about 2½ meters in height and then many hands helped bang in the 8 pegs into the earthy ground. I threw all my stuff inside, rolled out the cheap carpet to cover the grass and unpacked. In the tent, I got some privacy, but the kids were crowding around the door and frequently threatened to spill in. I set up a small kitchen with rocks to enclose the paraffin stove and balance my pans on. I put my blankets over the tent in the hope the sun might cause any parasites from last night to find somewhere else. As the shadows began to lengthen I was pleased I was ensconced in this idyllic setting with a fascinating and friendly group of nomads who I was in awe of already.

06. The zozan at the Hanging Valley zozan had 13 tents, or households, at it. Half were traditional woven goat hair tents, as pictured to the left, and the other half were more modern canvas ones., Ibrahim, on the mule, was taking dairy produce from his household down to Varegos to trade.

I cooked a meal in the tent as late afternoon merged into early evening. It was a perfunctory dish of rice and lentils, memorable for its bland taste. All the time men dropped by the tent to peer inside at me and there was a constant stream of children milling around at the door. I would have to put up with being a curiosity and in the spotlight for a while until my novelty wore off. There was a spell of activity outside as the women returned with their pails full of sheep milk. The sheep were further up the valley with shepherds. Then a bit later, near dusk, the goats arrived and the women had to go out again into a rough stone corral where the goats were gathered and milk them too. I think there were about 400 goats in all and there were 13 tents, or households, in total so each household had an average of about 20 goats to milk. I looked on as the women chased their individual goats in the herd, subdued them and then started milking them into different pails. The whole process took a good half hour and there was plenty of yelling, shouting and pointing with the younger family members helping to round up the goats. I learnt the goats would usually spend the night in the zozan, or camp pasture, while the sheep would remain in the more distant pastures in corals with the shepherds. All the milk would be put into large pans for the evening. Later that evening 3 of the younger men came into my tent for a chat and I managed to make them tea, and share my sugar and tobacco. It was mentally exhausting to try and make conservation with them, but they were alert, enthusiastic young men and there were no awkward silences. I felt much easier in the company of men and was shy and wary of the women. One of the men who visited was Hussein’s eldest son, Abdul, (left below) who had arrived that afternoon from Ikiyaka village with vegetables and wood on a mule, and was heading down to Varegös tomorrow, and another was Sabri who was returning to the village on short leave from his 3 year conscription in the Turkish army (right below). They left well after dark when everyone had returned to their tents and quiet settled over the camp. I rolled out a blanket as a mattress and crawled undo another two, pretty much fully clothed, for the night.

07. Abdul, another guest, and Sabri in my tent at the Hanging Valley zozan after I had just arrived in 1985. Abdul, on the left, was driving his household’s mules from Ikiyaya Village to Varegös taking pastoral products to trade and Sabri, on the right, was on leave from the Turkish military.

I woke at dawn and heard a rhythmic thudding sound from outside. There seemed to be few places where the sound was coming from. I was curious so poked my head outside and a few of the brightly dressed women were swinging a goat skin which was hanging from a tripod of 3 poles. The woman next to me was Guri, who was Hussein’s brother’s wife. She had one end of the skin and was swinging it backwards and forwards. She had two arms on a stick between its back legs and each time she swung the liquid in the skin sloshed backwards and forwards. I was more than curious and asked what was going on and learnt she was making butter (tereyagi). The milk which had been left in the large cauldrons overnight had partially divided with the cream coming to the top. This cream was scooped off and put into the goat skin, while the more watery milk remained in the cauldron. The neck of the skin was then sealed up with a wrap of rope so the skin was watertight. The goatskin was then swung backwards and forwards for about 20 minutes and it looked quite hard work. A pot was then put under the neck opening of the skin and the twist of rope was loosened off and opaque liquid started to pour out. When it was all out the neck was fully opened and a new pot, lined with a nylon sack, was put under the neck opening. Into it was scooped firm dollops of whitish fatty butter. Once the main blocks had been extracted a ladle was used to scrap the rest of the butter out. The sack was then tidied up and hung over the pot of opaque liquid to drip into it. This liquid was whey; which was milk with the fat extracted from it. The butter sack was then laid out on the grass beside the brook where it would dry off. The butter was essentially kept for frying food while the whey would be kept and mixed back into milk which was later destined for cheese and yoghurt.

08. Guri making butter in the goatskin in the early morning. The butter fat was naturally separated in the large cauldrons and then scooped off in the morning and put into the goatskins where it was churned until it formed butter and whey. In the foreground is the kapanak felt cloak I bought.

The goats which had been at the camp last night left as dawn broke and went back up the valley with some youths to look after them. I thought it would be interesting to go and see what they and the shepherds were up to. It would mean I could get away from the goldfish bowl of the camp where I was still the centre of attention. The floor of the U-shaped hanging valley I was in gently rose between sides topped with craggy ridges for a couple of km to reach a craggy head wall. I could see a path heading up through the outcrops of the headwall to what must be a basin beyond. The shepherds however were in the U shaped valley looking after some 400 sheep. Long before I approached 3 large kangal dogs came bounding towards me with intent. I reached for the large knife I had tucked into a sheath in my long socks and had it at the ready, but knew it would be ineffective against these three huge dogs, each a meter high and perhaps 60kg. The shepherds were shouting at them which took the wind out of their sails a bit and they surrounded me barking loudly, but not snarling and baring their fangs. I continued to walk towards the shepherds with the barking dogs escorting me. I returned my knife to its sheath as I approached the shepherds and the perceived danger from the dogs had diminished. These dogs were sheep dogs which spent their whole life among the sheep from an early age. They were there to protect the sheep from intruders, and also wolf, bear and even lynx which sometimes visit the area. The dogs walked me right up to the shepherds and delivered me to them making sure I did not stray towards the sheep grazing nearby. The three shepherds were very welcoming and had obviously already heard about me from the people who had passed through the camp and they started boiling up water for tea.

09.The shepherd Islam Dugran, Namen’s younger brother, and Aril Donat, Hussein’s son, watching the sheep in the hanging valley pasture. The automatic rifle Aziz is holding belongs to one of the village guards and is supplied by the Turkish Military to patrol the Turkey-Iraq border at the village.

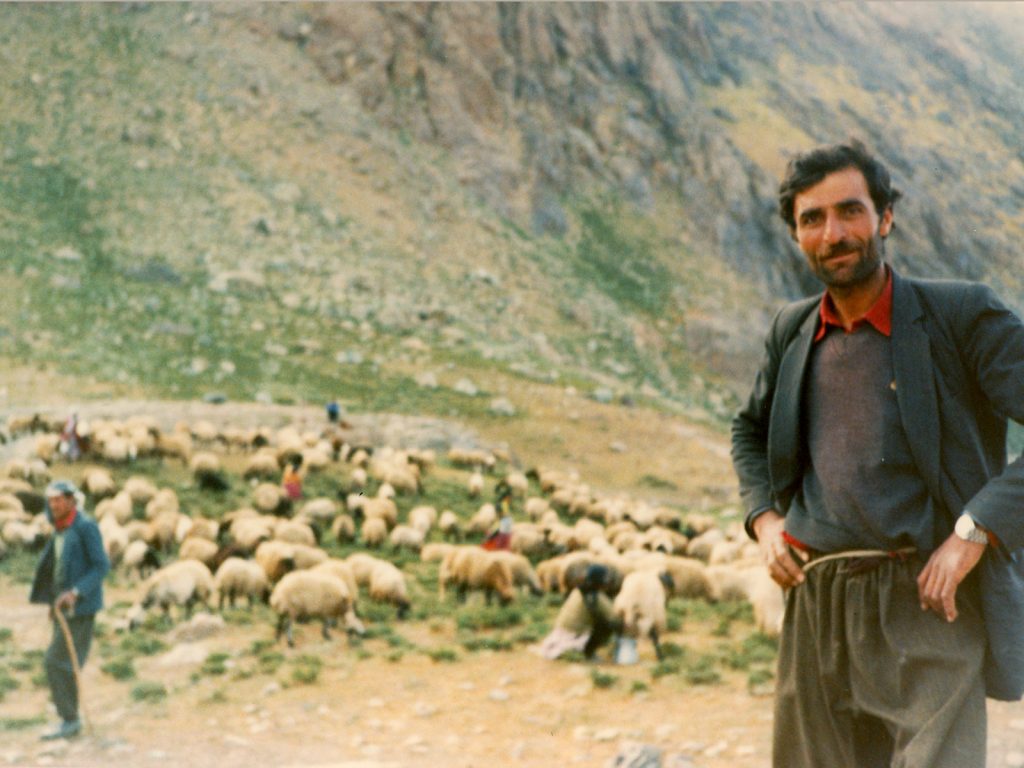

I learnt a lot about the herding from them. Idris seemed to be the main shepherd and he was accompanied by Islam and Ismail. Idris was the younger brother of Hussein, who seemed to be the most senior man in the camp I was staying at. There were some 60 households in Ikiyaka village and virtually all of them had sheep or goats. Because the land became so parched in summertime in the area around the village once the winter snows had melted, they had to leave and come up to these lush, ample pastures on the north side of the mountain. The 60 households split into 3 different herding units with about 13-24 families in each unit. The other two units were on different parts of the mountain half a day’s walk away. In this herding unit there were 13 households and they all pooled their animals into 2 herds, one of sheep and one of goats with about 400 animals in each herd. These shepherds looked after the sheep, who were quite placid and naturally tended to stay in a herd and remain on the lush pastures on the valley floor. At night they huddled up together in a rough coral and the shepherds remained with them while the three enormous Kangal dogs kept an eye on everybody. The goats on the other hand were much harder work and tended to wander off in all directions and did not have an instinct to gather into a huddle at night. They had to be kept together as a group and forced back to the nomadic camp each evening to more secure corals where the goatherds had to keep an eye on them. As such the goatherds seemed to be young men who had to constantly run around the hillside and then take it in turns each evening to stay awake and make sure they did not disperse. It was almost a kind of apprenticeship into herding. The shepherds had a much easier job and could relax for much of the day drinking tea and entertaining passersby. As such the shepherds were more senior men who had been through the rigours of goat herding in their youth.

10. Me in my typical Kurdish jacket and shalwar trousers and a pushi or Kurdish headscarf with the shepherds. The rifle was an ancient hunting rifle which the shepherds always had handy in case they needed to defend the sheep.

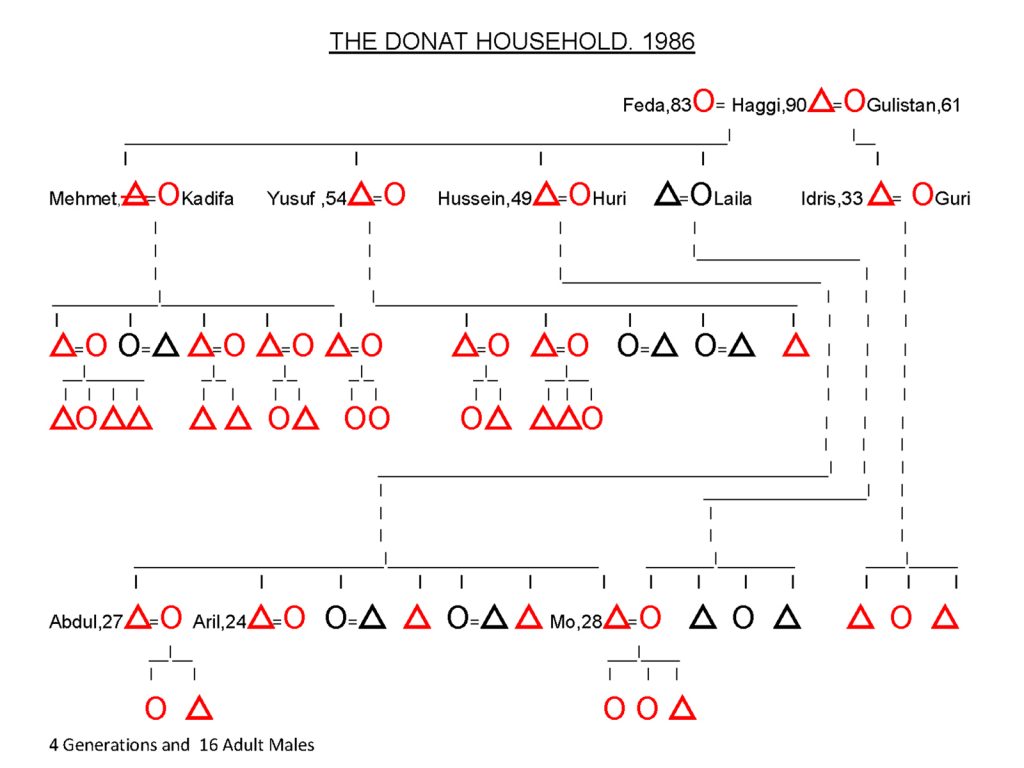

Idris, the head shepherd, was a member of the Donat household, one of the largest in Ikiyaka and they had 200 sheep and 200 goats, with the other 12 households having just 200 of each between them. As such the Donat family supplied a fulltime shepherd while the other families provided shepherds and goatherds on a rota, with a change over every week. Idris knew everything about the sheep. He not only knew who owned each of the 400 sheep but also knew each sheep’s family tree for a few generations. His decision on shepherding was final, so he would decide when the sheep needed to move to new pastures, which rams needed to be scarified at any festival to keep the breeding stock strong and he would deal with illnesses and infections by segregating some animals or even culling them. Islam was a member of the Dugran household and they had about 20 sheep and 20 goats. Idris also was responsible for the welfare of the goats but delegated to a rota of young goatherds. It is no problem for a household to have 100’s of sheep in the summer while everyone is at the summer pastures, but impossible for the smaller households to collect enough fodder for them to see them through the winter months when the snow covered the village to a depth of 2 meters. The Donat household had the manpower for 400 livestock but the Dugran family did not. It could only manage to collect enough for 40 animals..

11. Idris Donat was the head shepherd for this herding unit. His father owned half of the sheep and goats which were in the entire herd. He was always on shepherding duty, while the other households in the herding unit provided shepherds on a rota basis.

I chatted with the shepherds all morning until the women from the camp arrived. There were about 15 of them and they all came up the path in a lively noisy group chatting and laughing. They all carried a large aluminium pail and were coming up to milk the sheep and bring some lunch up to the shepherds. Guri, who was Idris’s wife, brought a sack of large nan breads and a small pail of stew. Guri, Hussein’s wife, Huri, and a few other young girls then started milking their 200 sheep while women from the other tents just had 10-20 sheep to milk. It was quite chaotic but everybody seemed to know what was happening. The women grabbed their sheep which they could recognize from the mass of the herd, squatted down beside them and quickly emptied their udders into their pails with a series of squirts. It took under a minute to do one. The sheep did not seem to mind and almost waited in line to get milked tending to cluster round their owners who would bride them with a bit of salt to lick. There were a few who were more reluctant, but they were quickly chased down by their dexterous owners who ran after them with a pail full of milk, skilfully catching them and subduing them. It was all over after 30 minutes and then the women all returned down the path with joyous fanfare and full pails, and calm descended over the pasture again as the shepherds boiled up water for another tea.

12. Idris Donat had been the main shepherd for the herding unit his household belonged to for a few years. He knew the family tree of all the 400 sheep in the herd, half owned by his household and half owned by the other 12 households.

After a good few hours with these 3 shepherds I saw the goats up on the hillside to the north of the valley. I left Idris, Islam and Ismail and headed up to the goatherds. As I left the kangal dogs started barking half heartedly and with just one command from Idris they stopped, circled the spot where they were lying, keeping an eye on the sheep, and lay down again. I went up the hillside towards the goats threading a route through the thorny scrub bushes which were scattered across the hillside. I climbed high above the valley floor up the side, and could see beyond the headwall at the end where there were some snow fields and a lake in a hidden basin. This area looked really inviting for tomorrow’s wanderings. As I approached the goatherds I had to go through the same fearful experience again as their three dogs embedded with the goats came bounding towards me. I did not pull my knife out this time but was still scared. The dogs were confident, just surrounding me and keeping a 5 meter distance, barking loudly to be certain the goatherds were alerted. They were bellowing at the dogs which seemed to appease them, and gave me some certainly to stride on confidently. Again there were 3 goatherds who were trying to stop the goats from scattering. One of the herders was up in the crags with a few of the goats who were in search of some lofty patches of grass among the small buttresses and gullies. The goats would have gone right up the crags and over the ridge line left to their own devices as they hopped and sprung nimbly up across the steep outcrops and the goat herd was throwing stones to divert them. I sat with the other two while the third got the more feral explorative goats under control and back down to the thorny scrub. We could never really stop and make tea or chat as the goats were always on the move, eager to find fodder and often passing by nourishing clumps just to keep moving.

One of the tricks the goatherds used to keep the herd from scattering was to roll rocks down the hillside, either behind them to hurry them along or more often in front of them to stop the leaders marching off. While I was there a goatherd rolled a grapefruit size rock to speed up the stragglers. The goats heard it coming and rushed forwards, but the youngest dog who was still a puppy really did not. Despite everyone shouting the young dog was oblivious to the missile and it glanced at his back leg. He let out a yelp and leapt forwards with a limp. I went down to see the dog which was lucky to escape with a small cut rather than a broken leg. Being of European disposition I felt sorry for the dog. I borrowed a rag from a goat head and wrapped it round the leg covering the gash. As I tied it up the dog turned and gently bit my forearm. It was not an aggressive bite, as even this young dog was a 30 kg mastiff and it could have done some serious damage to me. With the bandage in place we carried on with the afflicted dog limping gingerly behind. Eventually we got to camp in the late afternoon and the women emerged from the tents to milk their goats after they had gone into the coral. I returned to my tent and after a while Hussein came in. He obviously had heard about the dog incident and asked me about it. He said I had to go and wash in the stream as I was dirty. Apparently even touching the dogs was polluting, but to be covered in its saliva was disgusting beyond the pale. Perhaps these aversions are linked to their knowledge about rabies. Later that evening, after the women had milked the goats, emptied their pails into the large cauldrons, and then gone up to the shepherds to milk their sheep and returned with full pails again at nightfall, Hussein invited me into his tent for a meal. I had lots of tins of tuna so took a couple over to add to his food, which was nan bread and a thick gravy with lumps of meat.

13. Each herd of sheep and goats had a few large mastiff dogs embedded amongst the animals. The dogs would grow up with the herds and spend their entire time with them, always on the lookout. The fearless dogs would attack bear, wolf, lynx or human if they perceived a risk.

After being woken the next morning at daybreak by the rhythmic sloshing of the women making butter in the goatskins I set off to explore the lake I had seen yesterday. The goats had already left the camp with their herders and the dogs, including the injured one. I made my way up the valley to the shepherds. The dogs came bounding towards me barking loudly but as they approached they fell silent and escorted me up to the shepherds keeping an eye on me. I had tea and a chat with them before continuing up the valley to the headwall, where a path zigzagged up between the crags. At the top was a huge basin with a large, deep-turquoise, crescent-shaped lake across it’s floor. Surrounding the lake were some smooth bare crags and the greenest of pastures. Beyond them were high craggy ridges culminating in jagged peaks, many riven by deep gullies still full of snow, all rising up into a perfect azure sky. Large snow fields covered the mountainsides between the pastures and the peaks and from these small streams emerged and tumbled down the rocks sometimes in wispy waterfalls. It was the most unexpected paradise and I was astounded I had never heard of these mountains before in my now extensive travels around Turkey. I knew I had stumbled upon something really special here. I walked round the west side of the lake on the path and more and more peaks unfolded to the east. There was a brook which came down from a deep dark sunless basin to the south and flowed across the fan of a lush meadow which pushed into the lake. It was the lushest grass one might imagine and was full of the bright yellow globe flowers. I sat in the meadow and marvelled at the scene.

14. Above the Hanging Valley was a large basin, called the Sergera Basin, surrounded by jagged peaks, On the floor of the basin were some 5 lakes with Buyuk Golu being the largest. The path to Ikiyaka village went across the basin and up over the ridge under the cloud.

After a while I saw a mule train coming down the path from the skyline to the south. From what I had gathered this was the path over the mountain to Ikiyaka village which lay on the other side. As the mules approached I saw someone with a gun waving. It was Sabri who had been in my tent on the first night. He had been home and was now coming up to the pastures for a couple of days to fill his lungs. He was accompanied by his father Hajji, who was wearing a white turban. I knew straight away by his title and turban he had been on the once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca. This pilgrimage, which all Muslims are required to do, would have involved considerable expense and hardship for Hajji. It would have conferred respect from the other villagers as it shows he is both pious and wealthy. I sat and chatted with Sabri and Hajji for a good hour until another figure approached from the direction of the camp. It was Idris the head shepherd and he soon joined us. He had come up to see what shape the pastures were in and whether it was feasible to move the sheep up from the current pastures in the hanging valley below. He thought it would be less than a week before the current pasture was tired and the sheep’s milk production fell. Currently they were producing about a litre a day. We sat in the sun while I listened to the men chatting. I understood virtually nothing they said but could tell they switched from Turkish to Kurdish at a whim. Only when they asked me a simple question in Turkish would I have a hope of understanding and even then they often had to repeat or even rephrase it. It was a timeless morning and I could have been in any century at that enchanted place.

15. Sabri and Idris, the shepherds, chatting to Sabri’s father, Hajji, who was going to Varegös from Ikiyaka village. We all sat on the lush grass beside the largest of the lakes in the Sergera basin. At the far end of the lake was the location for Gaveruk zozan which remained vacant until mid summer.

As we chatted a few mule trains went up and over the pass and down to the village of Ikiyaka. The pass seemed just a short distance from the lake, perhaps just half an hour. I thought I would go up and have a look after I got tired from answering and asking questions, which was the only way I knew how to communicate, and it was mentally exhausting. After a couple of hours the party split up anyway with Idris returning to the sheep and Sabri and Hajji continuing down to the zozan where I had camped. There was a good path for me to follow up the gentle ridge to the pass. As I climbed up it more and more lakes appeared on the floor of this large alpine basin. To my west were two lakes, one of which was still covered in ice with snow fields covering the mountainside coming down all the way to the ice. These two lakes, and especially the upper one, were in a deep north facing corrie and were probably in the shade for much of the afternoon. To the east there were 2 more smaller lakes on the basin floor and they looked idyllic with large meadows surrounding them. As I neared the pass more and more of the mountains unfolded from behind the nearer peaks. This was going to be a fantastic area to explore.

It was an easy jaunt up the scrubby meadows of the hillside to reach the pass. The south side was much steeper, and much dryer and totally parched. I could see the path zigzagging down the initial few hundred meters until the slope eased off and then it wove down more gently across scree covered slopes and stony ridges until it met a dried up streambed, nearly 1000m below me. Beyond the dried streambed was the village of Ikiyaka. It was perhaps 2 km long from top to bottom and all the land on each side of the village houses, which were strung out along the valley floor, was irrigated. I had been told that the Iraqi border was just beyond the lower part of the village. Beyond it was just dry barren rocky ridge after ridge disappearing into the blue opaque haze of the obscured horizon. I am sure between these distant ridges there would have been some small streams, irrigated land and even small villages, but from up here it looked inhospitable and empty. Even the terraced fields of Ikiyaka looked dry and arid, but perhaps it was the ripening grain I was looking down on. It was too far to see the houses clearly but I could see a few beside the corridor of large trees which lined the streambed. The houses I could see were the typical single story flat roofed houses found throughout the region. Far below there was a mule train approaching the village and they were easy to see because of the wedge of dust the mules were producing.

16. From the pass to the south of the Sergera basin there was a long near 1000m descent down the south side of the mountain to Ikikaya village. A kilometre beyond the lower end of the village was the Iraqi border and most of the land above the centre line of the photo is in Iraq.

I returned down to the large lake where there was no one and just sat in the late afternoon sun enjoying the splendour of the area. I was enchanted not only with the landscape but also the culture of the nomads on the mountain here, which through my passing eyes looked idyllic, but I am sure was harsh. After a snooze on the flower filled meadow I headed down to where the shepherds were in the hanging valley beyond the end of the lake, which I realized had no visible outlet. A new shepherd, Namen, had joined the original 3. He was the elder brother of Islam who would be heading down to Ikiyaka tomorrow. I immediately liked Namen who had a gentleness to him which Hussein lacked. Namen was very forgiving of my fumblings in Turkish and kept suggesting words when I got stuck. As we were drinking tea I could hear the clamour of the women coming up the valley for the late afternoon milking of the sheep. This time instead of chasing round after the sheep with pails sloshing the women formed two rows facing each other with 8 in each row. With some encouragement from Idris, the head shepherd, the sheep then just formed an orderly queue waiting to be milked. Idris sat on a stone in the middle of the two rows of women and as the sheep slowly filed towards him he distributed the sheep to their respective owners who then milked them in an orderly manner, chatting enthusiastically and laughing loudly. All 400 sheep passed through and Idris knew which household every one belonged to. Again it took about half an hour until the evening milking was done and then the colourful enthusiastic group of women all left and headed back to camp swinging their nearly full pails.

17. Milking the sheep near the Hanging Valley zozan. This was the orderly way of milking the sheep where they lined up and Idris, the head shepherd, passed each sheep to the individual owners who milked their own sheep. There was usually one lady, but sometimes 2 or 3, from each household.

The next day I decided to explore a bit further, so I went back up with the women when they went up to milk the sheep in the morning. By now the 3 huge mastiff dogs were used to me and just let out a few half hearted barks without even bothering to get up. After the milking was over I had tea with the shepherds and then set off up to the big lake, which was called Buyuk Golu. I went round the south side of the lake passing through the meadows we had been at yesterday. Just beyond was a tunnel which the entire lake drained into and then plunged into the heart of the mountain in a swirling cascade. At the east end of the larger lake was a smaller lake which seemed quite shallow, as I could see many boulders in its milky azul waters. Just beyond this was yet another small lake. At the stream between the smaller lakes where many rings of stone walls which I guessed were the ruins of summer camps. I walked round the more gentle grassy south side of the lake and then climbed steeply up a headwall at the end which was still covered in large drifts of snow. Small wispy waterfalls cascaded down the headwall as I made my way up a natural ramp. At the top there was a great view across the basin to the west which I had just crossed. I however had just climbed into yet another higher basin and it had one shallow lake on its floor. To the east of this were stony slopes with a plethora of small animal paths formed by centuries, if not millennia, of grazing. I followed a series of them up to a high col on the skyline, where a magnificent view burst upon me. In the near distance, across a couple of spurs and gullies was the mountain of Samdi Dag. the biggest in the area and the second highest in the entire Cilo-Sat Range. It was nearly 4000m at 3811m. Its jagged ridges, still harbouring large snowfields, led up to a lofty pointed rocky summit. I could see a prominent path to the east, coming up the valley below me from Ikiyaka village, which then went over a col to the north side of this mountain. It must have been the path used by one of the other two herding units from Ikiyaka village to their summer pastures, or zozan, and then on to the rough road at Varegös.

18. The view from one of the easier peaks to the east of the Sergera basin looking east towards Samdi Dag, 3811m, the highest peak in the area. The path centre left is another way up from Ikiyaka village over the range at the visible pass and then down past zozans to Varegös

From the col I was on it seemed quite simple to climb up rocky slopes covered in tough, prostrate alpines to a broad peak. There was no path and I just clambered up the small stones and gentle outcrops in my sandals until I reached the top. From here I had a great view in all directions. Below me to the west were the lakes I had walked past a couple of hours ago and beyond them was a craggy ridge. The lower part of this ridge was where the goats had been grazing when the stone hit the dog. Beyond the ridge the landscape dropped away to the town of Oramar, or Daglica, deep in the Rubarisin stream valley before it flowed into Zap River. Finally beyond the valley was the massif of Cilo Dag, the highest peak in the entire range at 4100 metres. I was sure that on the north side of this mountain also there would also be groups of nomads taking advantage of the lush pastures afforded by the melting snowfields just as there were on Samdi Dag.

19. The view from one of the easier peaks to the east of the Sergera basin, below, looking west. The mountain in the far distance is Resko, the highest in the whole Cilo-Sat range at 4134m. Gaveruk zozan is between the lakes bottom right and Sergera zozan middle right near the barely visible lake.

By the time I got back to my tent via the shepherds for a glass of tea, it was late afternoon and the women were already heading off to milk the sheep. When they returned the goats were arriving for the night in the adjacent coral with the 3 goatherds and the dogs, one of which was still limping after the rockfall. One of these women, Fatima, was very confident and could speak some Turkish having been brought up on the plains around Yuksekova, before marrying someone from Ikiyaka. We had a few chats over the previous evenings. Her husband was down in Ikiyaka working in the fields and would be coming up in while to do his shepherding duties. In the meantime she was running her households tent up in the pastures and doing all the dairy tasks, and looking after her 3 children, one of which was only a year old. This evening just before milking the goats she came into the tent and put the baby down on my blankets. My tent was warm and she had her hands full. About an hour later she returned, sat down opposite me and pulled a plump breast out of her blouse. Then lifting the baby onto her lap started feeding it. I was wary and taken aback. In Kurdish society adultery is so frowned upon it is often punishable by death. If a married lady commits it then her original family will be so ashamed they will often murder her, with her brothers avenging the shame she has brought on them. Her husband’s family will also take revenge on the male perpetrator. So I felt quite uneasy and hoped nobody would come in and she would finish quickly. It was not to be as soon another woman arrived at the tent, and then a few children, and then Namen, the new shepherd came in. All the time Fatima kept breastfeeding without batting an eyelid. In fact nobody batted an eyelid except for me. I had a much more Western attitude to breastfeeding with breasts seen as sexual objects, than these Kurdish nomads who saw them as perfunctory appendages. In the following weeks while I stayed there, Fatima would often drop her baby off in the warmth of my tent while she milked the goats and cooked the evening meal for her household.

20. Some of the children and ladies from the Hanging Valley zozan. The ladies were the mainstay of the zozan and were responsible for all the dairy tasks. They also cooked and looked after the children. The lady on the right with the infant is Fatima.

As the time passed I slowly became less of a curiosity. I would still go and eat in Hussein’s tent every other night taking some of my supplies over to add to his food. The two women in the tent, Hussein’s wife, Huri, and Idris the head shepherd’s wife, Guri, were always busy cooking food, making tea, doing their dairy chores, and going back and forth to milk the sheep and goats. Over time I slowly managed to communicate with them through drawings in my notebook, sign language and what Hussein translated for them. Hussein’s wife, Huri, had considerable sway in the camp being the eldest woman there and also as Hussein’s wife. She had 4 grown sons and this gave her more authority and respect. Idris’s wife, Guri, was certainly the junior and had to do the lion’s share of the more menial jobs, together with whichever of Huri and Hussein’s daughter-in-laws who were staying up at the zozan. It was a busy tent with people coming and going most of the day as they passed through the camp en route between Varegös and their village. Hussein’s sons, Abdul and Aril were frequent visitors as they took turns in taking Hussein’s mules back and forth.

21.The path between the hanging Valley zozan and the Sergera basin was a few km. To leave the hanging valley the path climbed up the steep slopes to the right and over the lip of the basin. There were often children running errands who went between the camp and the sheep in the pasture.

The other tents were much quieter and I was seldom invited into them. It was largely because they were mostly occupied by women who had their family’s dairy tasks to do. Occasionally their husbands would appear either to do a stint of shepherding duty, or to take dairy produce down to Varegös and bring flour and supplies back up and over to the village. The children from these other tents formed a lively, wild, cluster who as a group were always excited and were often around me with each one trying to show off, often at my expense. There were about 20 of them in all and if they were out in force it was like an anarchistic mob. Occasionally I would walk with one or two up to the shepherds and then they were a delight, wanting to pose for photos, scribble in my books or show me things they found. On one occasion in the camp a group of younger children were crowding round the door to my tent when one of the elder boys pushed a few of them in. One of the girls fell on my stove and knocked the tepid water over. It was the last straw for him and I ran out of the tent, chased him across the marshier ground near the spring, and clipped him on the back of the head. He stumbled and fell face first into the soft mud, then got up and went off wailing. The women doing their dairy tasks had seen it all unfold and I was expecting some reprimand but instead there was laughter and approval. After that the rowdier children of the mob were more cautious and did not taunt me again and would sometimes come into my tent and quietly sat as I did my domestic chores.

22.The children in the camp at the zozan were quite an unruly mob. There were perhaps 30 of them and they got up to all sorts of games, but also mischief. I was occasionally the target of their mischief until I grabbed hold of the ringleaders here and reprimanded them.

There was always a strong smell of feta-style cheese around the camp. Once the milk had been collected the pails were emptied into large pans. Some would be destined for the butter churning in the goatskins every morning, some to make yoghurt which would be blended with water to make the ayran drink, but most would go into cheese production. In the evenings something was put into the cheese to make it curdle and in the morning it would have separated into curds and whey. The solid curds were scooped off, mixed with salt, and put into nylon sacks which were then tied up and left by the small brook emerging from the spring. They would lie in the warm sun with the curds draining until the feta style cheese was quite firm. Flies swarmed over sacks, sometimes they were so prolific the top side of the sacks were almost black. It would take the cheese in the sacks a good day to drain and form into feta. They were then taken down by mule to Varegös to be sold. The teenage boys who loaded the sacks and drove the mules stank of cheese, as when they manhandled the sacks they dribbled the rest of their watery whey onto their clothes, which were never taken off and washed. I frequently ate these cheeses as they were a staple dish with the meal every night, usually rolled up in a piece of nan bread. It was never my favourite especially when small gusts of wind swept through the camp and covered the dishes with a fine layer of dried dust, which was essentially powered goat droppings. Somehow in each of the months I was there for summer of 1985 and 1986 I never got ill.

23. One of Hussein’s younger sons was responsible for turning the feta cheese sacks as they dried in the grass beside the brook and also for loading them onto the mules. Whey dribbled out of them as they were man-handled and often onto the clothes of the young lads who stunk of feta.

During the day I spent more and more of the time with the shepherds, and often the goatherds also, although the latter was hard work as the goats were always on the move. In the evenings the goats returned to the camp while the sheep were collected into a coral and guarded by the 3 large dogs. The shepherds would have their evening meal brought to them by their wives when they came up to milk. They would eat their meal after the sheep had been milked and dusk fell, then build the fire for evening tea. When the sun dipped below the horizon the temperature plummeted. During the day it was perhaps 30 centigrade, but during the night it would be down to minus 5 and there was a frost on the ground every morning. The shepherds would huddle beside their fire in a small ring of stones beside the sheep coral drinking tea for a couple of hours until they went to bed. For bedding they just had a ‘kapanak’ which they withdrew into pulling it over themselves. A kapanak was a large cloak which was split down the front. It did not have arms but rested on the shoulders. They were quite heavy, about 4-5 kg, and entirely made of felt, perhaps a 4 square metres of it. The felt was made by collecting sheep’s wool and roughly twisting it together in small loose rectangular blocks. These blocks were then taken to the stream, soaked, and then beaten with a heavy stick to flatten the block into a sheet some 1-2 cm thick. It took a lot of beating to make one sheet with more wool being constantly added to the thinner bits. The sheets were then joined together with more loose wool packed around the periphery of each sheet which was again beaten until the sheets were one. When worn over the shoulders the kapanaks came down to above the ankles and were extremely warm, windproof, and I am sure waterproof. The shepherds slept in them by putting their head into one of the shoulders, then lay on the ground and pulled the upper side over them tucking it under their side which lay on the ground. Then by pulling bending their knees up the hem would enclose their feet enveloping themselves in a warm wrap of felt.

24.Two shepherds from Varegös in their felt cloaks. These felt cloaks were homemade from sheep and goats wool and were very warm. At night they tucked their head into one of the shoulders, lay on the floor and wrapped themselves in it. I bought one like this from Hussein.

Hussein had a spare kapanak and offered to sell it to me. It was much warmer than my blankets. It meant that after a week of being in the camp I could go and spend the night up with the shepherds. Idris was still the main shepherd and always was as his household had half of the animals in the entire herd. Islam was still there finishing his households duty rota, but Ismail had returned to the village, his households rota finished and he was replaced by Namen who was Islam’s older brother. Namen was very friendly and avuncular, not only to his brother, Islam, and Idris, but also me and indeed everyone including the rabble of children at the camp. While Hussein was always trying to maintain his authority in the camp and was constantly looking for opportunities, Namen was easy going, friendly and warm. They were delighted to see me pitch up with my kapanak at dusk. I had some food and we ate supper together and then huddled round the fire. Idris and Namen had a constant ear out for the mood of the sheep, while Islam made pots of tea. It was an evening filled with wonder and I felt like I was in a nativity play. The evening was like a scene from the Old Testament. A picture from a children’s edition which had come to life. Indeed this was a lifestyle which had probably not changed for the last 5000 years since man had domesticated sheep and goats. Humanity enjoyed this lifestyle for hundreds of generations until industrialization disenfranchised us from it. But here in a hidden corner of the globe was a pure relic of our past. For most of us this enchanting lifestyle is part of our cultural DNA shimmering just below the skin and it was easy for me to immerse myself into the time of the Prophets and pastoral parables. After a few hours when the sheep had settled, the dogs were alert, and the temperature dropped to zero under the crystal studded sky. I lay down on my new kapanak. I put my head in its pointed shoulder recess and pulled it over me. It was very warm and although I could feel the cold stinging my exposed nose the rest of me was snug in the cocoon of felt.

25. Islam Dugran was a regular shepherd and was often with the herd of sheep. He was one of the rota shepherds who helped Idris Donat. At night they slept near the sheep in a small coral of stones while the dogs watched the sheep. Before they went to sleep the shepherds always brewed tea

We all woke at dawn when the sheep were stirring. Idris went to check on them while Namen made a pot of tea. Down at the camp I imagined the rhythmic sloshing of the goat skins as the women churned their butter and the children were subdued and shuffling about rubbing their sleepy eyes. Perhaps most were still swaddled in scratchy blankets on a carpet on the floor of their black tents. I knew the women would arrive in a couple of hours with bread and food for the shepherds and a pail for the morning milking. As we were having morning tea in the bitter shade of dawn there was a discussion amongst the shepherds, then Namen told me Idris had decided to move the flock tomorrow up the mountain to the lush pastures at Sergera as the pastures here were getting exhausted. The animals each produced about a litre of milk a day and this would decrease if they continued to graze on these close cropped and browning pastures. The untouched pastures at Sergera were plentiful enough to see them out until the first of the winter storms arrived in October and sent both this herding unit and the other two on the mountain back to Ikiyaka for the winter. This was exciting news for me as I would witness the camp move and then set up again at Sergera. I did not know where Sergera was but knew it was up beyond the craggy headwall of this hanging valley and in the idyllic basin above with the lake surrounded by an amphitheatre of jagged towers. It meant a lot of the mules which were going backwards and forwards from Varegös to Ikiyaka would spend the night in the camp so they would be used to transport the tents the next day. After milking I returned with the women to the camp, as I too had to prepare to move my tent and belongings.

26. Islam Dugran with the sheep and his nephew, Namen’s eldest son. Islam had occasional epilepsy but I never saw it so he was seldom left alone and was unmarried. He was a gentle man and reminded me of a typical shepherd from an illustrated edition of the Old Testament.

When morning came the dairy chores were all done as usual with butter being churned and the cheese being prepared from the remainder of the milk. The tents were then quickly emptied and the possessions bundled up in old goat hair sacks or new nylon sacks. When everything was out the poles were taken down and tied up in a bundle and then the large black awning of goat hair matting which was the roof of the tent was folded into a long strip which was then folded up. It was remarkably big and bulky, but then it was perhaps 30 square metres. The 9-10 mules which were collected at the zozan for the move could not manage all in one go so had to make two journeys. Namen had arranged for a mule to take my tent and I managed to stuff the rest of my possessions into two large nylon sacks which I tied together and slung over my shoulders. I was my own mule. Half the camp went with the first load and half stayed behind and would come up with the next load in a couple of hours. There was excited chatter as we went up the hanging valley with everyone carrying something. Even the toddlers were playing their part and carrying empty milk pails or serving trays. We passed the pasture where the sheep had gathered each night and it was now empty, as the sheep had already moved off at dawn with the dogs and shepherds. We climbed the zig-zags at the valleys head wall and reached the basin. I knew the camp would be beside a lake but did not know which one and was surprised to see everybody heading to the smaller lake on the very east of the basin rather than the main lake, Buyuk Golu. We went to the far end of this lake just before the rise up to the lake which was still covered in ice. There were some stone circles here, upon which the black goat hair tents would soon be. pitched. Namen was already at the new camp called Sergera, beside the lake. He pointed to a nice flat grassy area near the stone circles where I could pitch my tent, but said it would be best to wait for Hussein.

27. In the centre right of the picture is the Sergera basin with its 5 lakes and two zozan, Sergera and Gaveruk. The herding units who ended the summer here came from the Hanging Valley zozan and one in the valley to the east of it respectively. The black lines are the paths from Ikiyaka to Varegös..

We did not have to wait long before the mules, Hussein and some of the girls arrived and I could see a colourful string of the children coming along the lake. Hussein said I could camp in the spot Namen showed me. The mules were all unloaded and their saddle bags emptied before they all turned and went back to get the second load. It seemed everyone had their respective place, probably where they camped last year. In no time the tents were unrolled and the fringes of the black goat hair tents were placed on top of the rings of stone walls. Then rocks were tied to guy line ropes. The shorter poles were then put on each side of the entrance to the tent and fixed with guy lines, then the longer poles were put in the middle of the tent to keep the roof up. It only took an hour before all the tents were up, including mine. Then stones were rearranged on the earth floor of each tent to make a fireplace and before long smoke was leaking out of the tops of the tent and palling in the still air above the camp as tea was made. Soon afterwards the mules returned with the final load and the rest of the camp arrived in excited groups all burdened down with pots and sacks which the mules were not carrying. Carpets and bedding were soon rolled across the floors of the tents and some 3-4 hours after the starting to dismantle the last camp in the Hanging Valley this new camp at Sergera was all set up and functioning. Most of the men were helping with chores to get settled in and were helping each other. Namen was busy helping everyone and I followed him around helping him. Fatima’s husband was still in the village and she had to do everything on her own, so Namen and myself helped put up her tent which was a modern metal pole and canvas one with many guy ropes and homemade wooden pegs. It was a jovial atmosphere and I am sure I heard some jokes with sexual innuendo from Fatima as the pegs were banged in, but I shyly ignored it while Namen laughed.

28. Namen Dugran and some of the children at Sergera zozan beside the higher lake. His herding unit of 13 tents moved here from the lower zozan in the Hanging Valley in August each year. One of the black tents behind them is the traditional woven goat hair tent of Hussein Donat.

By midday the whole camp was set up, food was being prepared by the women, and the men were discussing and smoking while sitting cross legged on the carpet in Hussein’s tent round a large tray full of tea glasses. I assumed an account of whose mule had carried whose possessions, and what the various mules would do now in the afternoon, either go down to Varegös or over the pass to Ikiyaka, were the topics. After lunch the women, who were always busy, headed off to the sheep, who were grazing nearby and had not been milked yet. Half an hour later they were back to pour their pails into the large pots to start the dairy process off again at the new location. With my tent set up I went for a walk to the Idris, Namen and a new shepherd who had replaced Islam. The sheep were grazing on the south side of the main lake enjoying the lush ungrazed grass while the shepherds were sitting on a boulder basking in the sun. It was a biblical scene again, but in this unrivalled setting. It was a paradise, with the bountiful flower-filled meadow full of green grass beside the shimmering lake, and all beneath a cirque of high peaks, each looking over their neighbour’s shoulder as if in frozen curiosity. This really was the land of milk and honey which I previously could only imagine. Here I was living in the midst of it with the most noble and hospitable pastoralists, with a seemingly idyllic and sustainable lifestyle which was as old as the scriptures.

29.The sheep grazing the new pastures in August between Sergera lake and Buyuk Golu lake, seen in the picture. Another herding unit from Ikiyaka village arrived about the same time each year at their zozan at the east end of Buyuk Golu lake (far end) which was called Gaveruk zozan.

I went for a walk with Namen to the smaller lakes to the west of Buyuk Golu Lake. He explained to me that the stream which drained the lake and plunged into the steep, dark shaft heading towards the heart of the mountain later emerged again on the south side of the mountain just above the village of Ikiyaka and it was the lifeblood of the village and allowed them to irrigate their lands. Beside the other two smaller lakes, beneath a band of steep rock over which wispy waterfalls cascaded were the pastures I had seen a week ago when I went up the peak ahead. Namen showed me the stone circles in an idyllic spot between these lakes and explained that another of the herding units from the village would be moving here in the next week or so when their current pastures were exhausted. This zozan was called Gaveruk and the pastures around it were reserved for their herds. There seemed plenty of grazing up here for everyone.

When we returned to Idris and the other shepherds a small group had gathered. One had an old rifle with a worn and polished stock which had many ancient wounds in the wood. A small flock of ducks had landed in the middle of the lake some 200 metres away and they were preparing to have a shot at the peaceful raft of them. Sabri was amongst them and he took the first shot. The sights must have been previously knocked as the bullet splashed into the water some 10 metres to the side. The ducks remained blissfully unaware they were being shot at and continued to preen themselves. It took about another 10 shots, each one getting closer as the sights were adjusted, before one duck was flung into the air as it was hit by the rifle bullet and killed. Unfortunately, the other ducks still remained unaware of what was happening and continued to preen. After another 20 shots two more ducks were dead and the other dozen had at last flown off. The trouble for the hunters was the ducks were still in the middle of the lake and there was no wind. Namen asked if I could swim and soon I was down to my underpants and knee deep in the freezing water plucking up the will to overcome the cold and swim out and retrieve the ducks. I don’t think they thought I would really swim out to get the duck as when I returned 10 minutes later they were incredulous. So incredulous they gave me one of the ducks. I returned to the zozan in triumph with it and Hussein arranged we would eat it that evening, giving to his wife, Huri, to pluck and prepare. Namen arrived an hour later and told the story how I swam out to retrieve the ducks to the camp. I felt like a schoolboy whose teacher had just sung his praises to his parents. About 6 of us shared the duck that evening which Huri had cut into small pieces and fried, almost beyond recognition. The new camp was in an idyllic location beside the small lake, but the very steep ridge to the south west plunged the camp into the shade in the late afternoon so the nights here were a bit colder.

30. Sergera zozan was the camp and herding unit I spent most of my time with. They moved here from the Hanging Valley each August and I moved with them. Just above Sergera was a lake which remained ice covered through the year. Beyond the far ridge is the steep descent to Ikiyaka village.

I spent about 2 weeks of my stay in 1985 camped beside the cluster of tents at Sergera. Much of the daytime I spent with the shepherds who were usually around the western half of the largest lake Buyuk Golu. It was a very sociable place as it was also on the path between Varegös and Ikiyaka near where it crossed the main ridge. The shepherds rotated a couple of times during these weeks but Idris always remained. One of the visitors was Yusuf. He was the elder brother of Hussein and Idris, and was eldest son of their father Haggi Donat, Haggi was reputedly 90, but I’m sure there was some licence in the figure and he was probably a little under 80. Haggi who I had not met apparently commanded considerable respect in Ikiyaka as he was formerly the village Agha, or headman, he had also been on the Hajj to Mecca, and he had 2 wives, 4 sons and 14 grandsons and many great grandchildren. Yusuf, I think, had just come up to have a couple of days in the zozan, which must have felt like a liberation after spending much of the summer in the parched heat of Ikiyaka village where he ran the household for his elderly father. In his earlier years Yusuf also spent much of the summer in the zozan and I am sure he missed it’s lifestyle

31. Yusuf Donat was an occasional visitor to the zozans but spent most of the time in the village with his elderly father. His brother Hussein Donat was the leader of the herding unit when they were in the mountains. In the near distance, just before the band of cliffs is Gaveruk zozan.

A few of the boys used to play in the water on the lake’s edge occasionally. After my now infamous swim Hussein asked me if I could teach some of them how to swim. The water was cold as it was largely snow melt. Although the air was perhaps 30 Celsius during the day, it was often just below freezing at night to counteract this. Where the small brook entered on the west side the water was slightly warmer and there was a small alluvial fan to wade in across. Nobody could swim as there had never been the need, but the boys were eager to try. I spent an hour a day wading about the shallows trying to teach 6 boys. Despite the water temperature they threw themselves into the water and splashed around hopelessly keeping within their depth. It was a testament to their hardiness they braved the water for so long. After a week they had calmed down and were able to float and do a simple breast stroke. I never had to find them at the start of the swim session as they started badgering me for their lessons after their camp and dairy chores were finished. Virtually all the children had household chores to do and it was amazing to see how a five year old could separate the curds from the whey and put the curds into the sacks and carry them to the brooks edge to mature into cheese. The young girls were already helping to milk the sheep and goats at five years old. They were keen to please their mother or elder sister who was in charge of the household dairy. If they fooled around, spilt milk, or were difficult they were quickly reprimanded with a shout or slap on their hand. To me it was unfathomable that such young children could be eager and effective on tasks which needed some competence. It would be a rare sight to see a 6 year old girl wrestle a goat into position and then milk her in Europe

32. After I had swum in the lake to retrieve some ducks which were shot by the old shepherd’s rifle Hussein persuaded me to teach some of the boys how to swim. Despite the freezing temperatures they managed to stay afloat with a simple breaststroke after a week’s worth of lessons.

Most of my conversations were mundane and were often initiated by me asking a question about the dairy tasks, or sheep or who was related to who. Occasionally the topics were more worthy and there were discussions about religion, geography, or astronomy. The Kurds of Ikiyaka were all Muslims. Namen, along with many of the others prayed five times a day. If he did not have his small carpet to hand when shepherding he laid out his jacket and faced the south towards Mecca at the appointed hours. In fact Namen even kept his watch at Mecca time rather than Turkish time which was an hour behind. I always choose to say I was a Christian rather than an Atheist as this would have been unnecessarily insulting. We would discuss the Prophets, which both Christians and Muslims shared as indeed did Jews. Abraham was the first prophet in all three of these monotheistic religions but held a more prominent place amongst these Kurds that he did in Judaism and the Christianity I was familiar with. Perhaps it was the pastoral lifestyle which these Kurds shared with Abraham which made them so fond of him or perhaps it was because he was God’s first Prophet. Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, Ismail, in obedience with God’s wishes, before God sees Abraham’s devoutness and provides a goat instead for him to sacrifice is the basis for an important festival, namely Eid al-Adha. In 1985 I was largely unaware of it until I noticed Idris, the head shepherd, separating off about 20 sheep and goats which were going to go down to Ikiyaka village the next day to be sacrificed a few days later in ritual commemoration of Abraham’s piousness.

Most of the other prophets of this Judeo-Christian-Islamic were also familiar to both these Kurds and me. The difference being my interpretation was that the prophets stopped with Jesus, the son of God, who they called Isa, while their interpretation was that Isa was just another prophet and not the son of God. Mohammed who lived 700 years after Isa (Jesus) was the final prophet and the Quran was revealed to him by God through the Angel Gabriel. In these discussions I did not argue any points, but rather acted as naive and wrote their interpretations in my notebook. Where I was slightly more convincing was my explanations of the mountains and lakes, why the sun and moon rose and fell and the shape of the earth. Again my notebook came out and I used drawings to illustrate how the glaciers had been much bigger once and had gouged out the landscape or how the limestone had eroded subterranean passages into which the stream from the lake followed or how the planets revolved around the sun and earth, which was round and not flat. Hussein had an enquiring mind and it was usually with him I would discuss things. He would then later relay them to others at the meal and I would have to rejustify my explanations as we sat on the floor eating dinner. It was usually met with scepticism as there was a thought that things had always been as they were since the Creation. These discussions always left me exhausted as my Turkish was just not good enough to discuss such lofty topics. However the use of the notebook to help communication was invaluable and I would have been lost without them. The discussions were always friendly as I was always aware that I was on thin ice and was never dogmatic.

33. Hussein with Hodgir. Hodgir was the village teacher and Iman and was quite political. His household had a tent in the herding unit where his wife and children spent the summer doing the dairy tasks. He always dressed in like a peshmerga.

There was a school in the village and the teacher was called Hodgir. He was one of the few political people had come across up here. I did not get into any meaningful conversation with him about the Kurdish situation but you could see he was a patriotic Kurd, much more so than the others. He dressed in the same style as a Peshmerga from the KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party) which was a much more liberal independence movement compared to the PKK. If Kurdistan was mentioned in a discussion he would cross his clenched fist across his chest. His family was at the Sergera zozan and he came up frequently but I never saw him shepherding. Perhaps as the teacher he was excused from the shepherding rota, as say a Catholic priest might be. When he was at the camp he spent much of the time with Hussein. Both of them were quite serious characters which could have been due their responsibilities, or perhaps they choose responsible roles because of their seriousness. I also heard people refer to Hodgir as Imam as he was very familiar with the Koran and its Surahs. I did not discuss religion with him as I was on thin ice and he was authoritative and would have considered me ignorant at best, or a blasphemous infidel at the worse. It was necessary to remain on the right side of Hodgir. He had a young son with blonde hair and blue eyes, which was not unusual and many people had green or blue eyes, especially the women. Kurdistan had for millennium been a crossroads of peoples and gene pools so Hodgirs’s son was not unique.

34. Hodgir with his son at the Hanging Valley zozan. There were many people from Ikiyaka and in the surrounding villages with blue eyes or blonde hair and Hodgir’s son had both.

After about a month with the Kurds of Ikiyaka on the north slopes of Samdi Dag my supplies were running out and I had completely overstayed the permissions which the Military Gendarmerie and the Commando’s had given me. I felt I was still welcome at Sergera zozan with Hussein becoming a patron-like figure and Namen keeping me under his wing. In hindsight I learnt there was little trust between the Kurdish villagers of Ikiyaka and the various factions in the lawless lands of Northern Iraq just beyond the villages boundary. The most infamous faction was the PKK, a soon to be terrorist organization whose ultimate goal was to capture all the historic Kurdish lands in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria and unite them into one country under a Marxist regime. Turkey, having the largest area of Kurdish lands and population, was the PKK’s primary target. But unfortunately for the PKK, Turkey was a well organized country with a massive well equipped army, including some 2 million conscripts. All the Kurdish men from SE Turkey were obliged to sign up for 3 years, as were all other Turkish citizens. The Kurds did so, some grudgingly and some willingly, and were often posted to Western Turkey. As a result they developed some patriotism and few had the stomach for a fight with Turkey. Most just wanted to get their service over and done with and return to their homelands. With increasing border raids by the PKK the Turkish Military recruited village guards for many of the villages along the Iraq border. These local Kurdish men were trained in the Turkish Army and then returned to their village with a salary and a supplied assault rifle. The village of Ikiyaka had a few village guards, who spent most of their time in the village as this was where any insurgency would first come from. Occasionally they would come up to the zozans on the north of the mountains just to see what was happening. I only met one of the village guards at Sergera zozan and he was called Sadi. He looked an extremely hardy and fearless character with his assault rifle over one shoulder and a bandolier over the other and in full Kurdish regalia. He was exactly the sort of man that the Turkish military would want to recruit and I should imagine the type of man the PKK would also be interested in recruiting, but his allegiances were already spoken for.

35. Hodgir with Namen’s son. Beside them is one of the village guards, possibly Sadi Aykut, who was visiting Sergera. Sadi was associated with the largest herding unit along with the Muktah’s household beyond the ridge some 3-4 hours from here. I did not visit and knew little about them.